Dilyara Kaidarova (Left), Member, National Academy of Sciences and Head, Almaty Oncology Centre and Gulnara Kunirova (Right), Director of Kazakh Institute of Oncology and Radiology and President, Kazakhstan Palliative Care Association

In Kazakhstan, palliative care requires more attention and support on the part of health-care administrators. Up to 98,000 patients are in need of palliative care interventions annually, over 6,000 professionals should be trained to cover this need, and more than 825 palliative care beds should be available for patients. The main problems in the current development of palliative care in Kazakhstan include: 1) limited access to opioids and inadequate pain management; 2) lack of trained personnel (including non-medical specialists); 3) limited hospice and palliative beds availability and underdevelopment of in-home and out-patient day care services and 4) lack of knowledge and prejudices among medical workers and the general public.

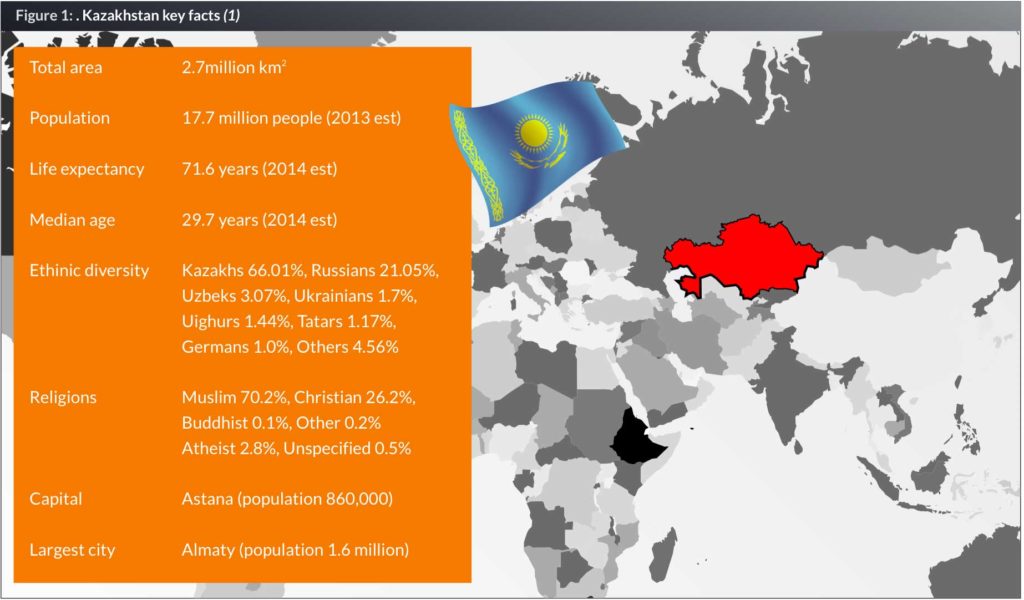

Kazakhstan is a landlocked country located in Central Asia, south of Russia and northwest of China. Given its large land area (equivalent to the size of all Western Europe), its population density is among the lowest, at less than six people per square kilometer (15 people per sq. mi.). Kazakhstan is a rapidly growing economy (GDP per capita: US$ 13,000 – up by 19 times since 1993) with vast mineral resources and large reserves of petroleum and natural gas (Fig.1).

In Kazakhstan, palliative care is only beginning to be recognized as a significant part of the national health-care system. The growing statistics of cancer incidence (about 30,000 new cases annually, and the incidence rate increases every year by 3–5%), and the heavy percentage of advanced stages (44.2%) imply the necessity of developing a comprehensive system of palliative care for incurable cancer patients. In addition to 144,000 registered cancer patients, there are about 23,000 people with tuberculosis, about 8,000 of which have multi-resistant forms. The number of people living with HIV in Kazakhstan is 20,000.

While no official registry of people requiring palliative care exists in Kazakhstan, the estimated need was calculated in 2012 by Thomas Lynch, an international palliative care consultant, at the level of 94,200 to 97,900 patients annually, with a minimum of 15,500 patients using the service at any given time. In addition, as there are usually two or more family members directly involved in the care of each patient, care would be given to a minimum of approximately 282,600 people annually. To provide home-based and inpatient palliative care to this extent would require substantial reallocation of health-care professional resources for both the urban and rural areas; approximately 6,675 staff and 825 palliative care beds would be required for this need to be fully met (2).

Milestones in the development of palliative care in Kazakhstan

The first hospice was opened in Almaty in 1999, and within the next three years hospices were opened in five other cities: Pavlodar, Karaganda, Kostanay, Ust-Kamenogorsk and Semey. However, the legislative base for the further development of palliative care took shape only ten years later, with the formal inclusion of palliative care in the remit of the overall national health-care system by the Code on People’s Health (2009) and the State Programme on Health-care System Development (2010). Elaborated within the framework of this state rogramme, a new National Cancer Control Programme for 2012–2016 for the first time included palliative care development indicators.

By 2012, basic legal acts and regulations were issued, that established categories of patients eligible for palliative care, categories of medical and non-medical professionals involved in providing palliative care, public health-care institutions and hospital units responsible for the organization of services, material supplies, documentation, etc.

Much progress in the development of palliative care in Kazakhstan was made during recent years through efforts of many highly committed individuals and organizations. The first comprehensive needs assessment report by Dr Lynch in 2012, financed by the Open Society Foundation Public Health Program, triggered the elaboration of the document regulating palliative care. Joint work by Kazakhstani and international specialists from the Soros – Kazakhstan Foundation, the Republican Center for Development of Health Care (RCDH), the Kazakhstan School of Public Health (KSPH) and a number of local NGOs and individual advocates resulted in the approval by the Ministry of Health and Social Development in December 2013 of the national standards for palliative care.

It is important that the document establishes not only public health-care settings, but also non-governmental organizations as palliative care providers. Palliative care is no longer regarded as a pure medical issue, but as a sociopsychological service as well. Now palliative care can be provided not only in hospices, but also in outpatient clinics, or at home by mobile multidisciplinary teams. For the first time, bereavement support is included in the context of palliative care. The standards also highlight the role of volunteers and families in providing palliative care, and oblige palliative care providers to consider educational, legal, social, and psychological support in addition to symptom control and pain relief. Special attention is given to paediatric palliative care: psychological needs of terminally ill children are mentioned separately, and their families are named as beneficiaries of palliative care services (3).

An important milestone was the creation in 2013 of the Kazakhstan Association for Palliative Care (KAPC) by the initiative of four NGOs: Together Against Cancer Foundation (Almaty), Credo (Karaganda), Adamgershilik (Temirtau), and Amazonka (Taraz). The Almaty Oncology Centre, the Almaty Centre for Palliative Care and a number of local NGOs joined the Association shortly after its creation, and now the organization takes a leading role in palliative care development in Kazakhstan.

The above mentioned NGOs are successfully implementing in-home palliative care projects in their respective regions, which, along with extensive educational, training and awareness-raising activities of all KAPC members, allowed for palliative care development issues to be included in the agenda of Parliament sessions, ministerial meetings and oncology congresses.

Current challenges and the way forward

The main problems in the current development of palliative care in Kazakhstan include: 1) limited access to opioids and inadequate pain management; 2) lack of trained personnel (including non-medical specialists); 3) limited hospice and palliative beds availability and underdevelopment of in-home and outpatient day-care services

Opioid availability

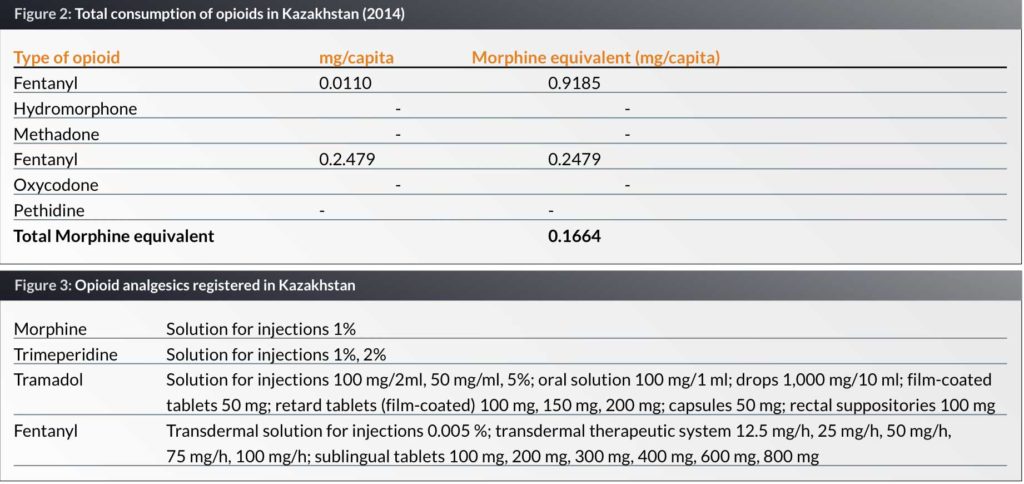

There are many barriers limiting the availability of opioid analgesics and efficient pain treatment in our country. Kazakhstan is among countries with the lowest consumption of opioids for medical and scientific purposes (Fig. 2). This problem derives from the use of an obsolete estimation method for demand of narcotic analgesics. It is necessary to increase the country’s quota for opioids at the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) (4).

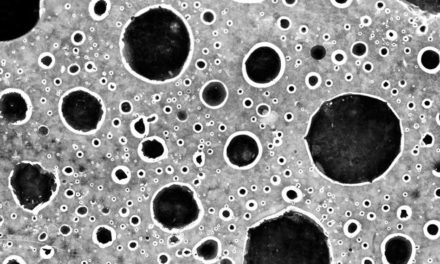

The range of strong analgesics in the National List of Medicines is very limited. Oral forms of morphine, recommended by the WHO as the “gold standard” for severe pain management are not available in Kazakhstan; the list of available medicines mainly includes intravenous forms that cause additional suffering to the debilitated terminal patients (5) (Fig. 3).

At least two foreign pharmaceutical companies have started the registration procedures for tablet forms of opioids in 2015, but local producers who were encouraged to start the production of inexpensive morphine tablets, are restrained by their concerns of excessive inspections by controlling agencies.

Kazakhstan has very strict procedures for licensing, transportation, storage, administration, prescription, issuance and disposal of opioid analgesics. Patients do not pay for prescribed opioid analgesics in Kazakhstan, but only a small number of pharmacies and health-care organizations are licensed to perform such kinds of activity.

The list of health-care professionals authorized to prescribe opioids is limited. Restrictions concerning the correct “writing” of a prescription, special prescription blanks, counter-signature by a chief physician, a requirement to return used ampules, packs, etc. creates an additional barrier for adequate pain management in cancer patients. For the patients from remote regions the receipt of opioid analgesics becomes a big challenge. Excessive controlling procedures, unreasonable prescription regulation and obsolete methods of disposal of narcotic opioids should be revised based on the best international practices.

While the average morphine dose in developing and low-income countries is 60–75 mg of morphine per day/per patient, the average daily dose in Kazakhstan does not exceed 30-40 mg. This problem reflects lack of knowledge among medical practitioners about opioid drugs administration and pain management. Opioid-phobia is a common phenomenon among doctors who are often ignorant of the difference between addiction and tolerance and are prone to prescribe low doses inadequate for the pain suffered.

The above mentioned and other issues connected with access to pain treatment in Kazakhstan were discussed at the conference on “Palliative care – new quality of life” and at the roundtable on “Accessible opioids – the right of everyone” that took place in Astana on 23 October 2015 and brought together representatives of the Ministry of Health and Social Development, Committee for Combating Illicit Trafficking in Drugs and Drug Control of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, Members of Parliament, international experts, oncologists, NGOs and local palliative care champions. A working group was created in order to find ways to eliminate barriers to access to opioids and adequate pain treatment in Kazakhstan. The Roundtable Resolution signed by all participants suggest-ed a number of changes to the normative acts, and the new Ministerial Order on opioids is expected soon.

Knowledge gaps

Another big challenge is low level of knowledge about palliative care amongst both society and the broader medical community, alongside an enormous need for palliative care services in Kazakhstan in relation to the limited number of educated trainers.

A number of excellent palliative care education and training initiatives were undertaken in Kazakhstan with the support of international and local organizations. From 150 to 200 palliative care enthusiasts, including physicians, nurses, psychologists, social workers and NGO leaders, participated in ELNEC courses, Salzburg Seminars, European Pain School courses and other globally known training programmes. Many of them visited hospices and palliative care departments in medical facilities abroad. At least three workshops on palliative care and pain management organized by KACP with the support of Middle East Cancer Consortium, American Society of Clinical Oncology and US National Cancer Institute will take place in 2016–2017. But these educational efforts undertaken mainly by non-government palliative care champions are still insufficient to cover the growing need for palliative care professionals across Kazakhstan

The problem of specialist training has to be acknowledged on the government level. The National Classifier of Professions does not include specialties like “palliative care” or “palliative medicine”. The lack of legislative basis for inclusion of palliative care into the national education standards prevents the introduction of training programmes into medical education institutions.

A methodological base, teaching standards and evaluation process for training medical (physicians, nurses) and non-medical (social workers, psychologists) specialists in palliative care should be developed and implemented on three levels:

- Basic (pre-graduate) level – for those who will be professionally engaged in medicine;

- Middle (post-graduate) – for specialized doctors who will encounter palliative care issues in their practice while not being a specialist in this field; and

- Advanced – for those who choose to become specialists in palliative care.

Since 2011, an elective course for fourth-year medical students and interns has been introduced at the Karaganda State Medical University. This curriculum was developed with assistance of Polish colleagues, and can be proposed to other higher educational institutions or to the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan.

The palliative care projects at the Asfendiyarov Kazakh National Medical University are focused on geriatric patients and include the development of an organization-functional model of home-based and hospital care of geriatric patients and development of clinical protocols for palliative care. Short-term training courses are organized on an irregular basis by such educational institutions, like the Kazakhstan High School of Public Health and Kazakh Medical University of Continuous Education.

The vast experience of non-governmental organizations and internet-based resources managed by them (for example, the site of the Kazakhstan Palliative Care Association – www.palliative.kz – where a Russian language library of educational materials was made available to anyone interested), may be a useful aid in organization of palliative care personnel training.

It is advisable to organize training centres on the basis of hospices to train doctors, nurses, psychologists and social workers in palliative care essentials, symptom management, pain treatment, etc., as well as ward attendants, volunteers and family members in the practical skills of nursing and psychological assistance.

Availability of palliative care beds and outpatient services

The Cancer Care Development Plan for 2012–2016 provided for the establishment of palliative care centres in the cities of Astana, Petropavlovsk, Aktobe and Kyzylorda in 2013, and opening of palliative care beds cancer centres in Taldykorgan, Almaty, Uralsk, Atyrau, Shymkent, and Taraz from 2014 through to 2016. To date, about 150 new palliative care beds were opened in accordance with this plan.

Today, inpatient care is provided by 11 facilities, including hospices, nursing homes and departments of symptomatic treatment and palliative care. The total number of beds does not exceed 500, which is insufficient for a nation with the population of almost 17 million people.

In addition, availability of inpatient care for patients living in remote settlements is not feasible. It is appropriate to develop outpatient and home-based forms of palliative care in rural areas and small towns.

Patients with advanced-stage, incurable cancer discharged from an oncology centre or hospital fall under the care of a municipal outpatient clinic. Their care becomes a responsibility of general practitioners and staff oncologists, who are not properly skilled in palliative care to address the medical, psychological, social and spiritual problems of these patients. They usually do not have the necessary resources (transport, support of a multidisciplinary team, skilled nurses, psychologists, social workers, volunteers, special care products, medicines, consumables, etc.).

Four NGOs, Credo in Karaganda and Temirtau, Amazonka in Taraz, Together Against Cancer in Almaty and Solaris in Pavlodar have trained multidisciplinary teams and started in-home palliative care projects for incurable patients. In Almaty, the project has been initially financed by Soros – Kazakhstan Foundation, and since this year the mobile team became a department of the Almaty oncology centre. In addition, the Almaty Palliative Care Centre started its own mobile team. With these projects a sustainable model for home-based palliative care has been established in Kazakhstan that can be further promoted for implementation in other parts of Kazakhstan.

The development of mobile teams contributes to the need for integration of cancer treatment, primary medical care and palliative care services that are administratively separated. It also opens opportunities for patients to get broader access to consultations with oncology specialists, diagnostic facilities and minor surgeries.

But underlying the above mentioned barriers there is major problem of lack of understanding amongst general public and medical community of the philosophy and practical advantages of palliative care for the suffering people and the whole health-care system.

Conclusion

Even with some positive changes in place, there is a lot of work ahead, in terms of capacity build-ing, strategic planning and advocacy. The Kazakhstan Association for Palliative Care was created with an intention to put together efforts from all local champions, from Members of Parliament to volunteers; international experts like Thomas Lynch, Mary Calloway, James Cleary, Thomas Smith, Michael Silbermann, Stephen Connor, etc.; partner organizations, like Open Society Foun-dation, IAHPC, EAPC, UICC, ASCO, NIH/NCI and many others, in order to speed up the process of developing palliative care in Kazakhstan.

Biographies

Ms Gulnara Kunirova, Master of Psychology, joined the anti-cancer movement in 2009 when she took a position of the Executive Director of the Together Against Cancer Foundation – a non-profit, non-government organization aimed at the improvement of cancer care in Kazakhstan including efficient prevention, high quality diagnostic and laboratory services, excellent professional care, wide range of tested and proved medications, necessary psychological, legal and social support, accessible rehabilitation and palliative care.

References

1. http://www.kazakhembus.com/content/quick-facts-0#sthash.WPjVcbYN.dpuf

2. Palliative Care Needs Assessment, Republic of Kazakhstan, Thomas James Lynch, PhD, Open Society Foundation Public Health Program, International Palliative Care Initiative (IPCI), October 2012

3. Kazakhstan: National Palliative Care Standards approved, Ainur Shakenova, Law Reform Program Coordinator and Palliative Care Development Coordinator, Soros Foundation-Kazakhstan, February 28, 2014, http//www.ehospice.com

4. Interactive Opioid Consumption Map https://ppsg.medicine.wisc.edu

5. Order of the Minister of Health of the Republic of Kazakhstan, dated September 9th, 2011 #593 On Approval of National Drug Formulary (with amendments and additions as of April 12th, 2013)