Rowena Tasker, Global Advocacy Manager, Knowledge, Advocacy and Policy Team; Philip Martinez, Knowledge, Advocacy and Policy Team and Dr Sonali Johnson, Head of Knowledge, Advocacy and Policy, Union for International Cancer Control (UICC)

As the global population experiences a “longevity revolution” health systems around the world will need to respond to a rapidly increasing number of geriatric patients, yet few of these health systems appear prepared to respond to the unique needs of this population. Exploring the approach adopted by the palliative health community can help understand what opportunities this model might afford as we work to scale-up patient-centred, participatory care for older people with cancer.

Globally, there is a “longevity revolution”taking place in which the world’s population is ageing rapidly. There are currently over 703 million people worldwide above the age of 65 (1) years equating to 9.1% of the global population, and estimates suggest that the proportion of the population over the age of 65 is expected to rise to 15.9% (1.5 billion) by 2050 (1). The fastest growth is likely to be seen across the least developed countries, where the population of over 65s is projected to grow from 37 million in 2019 to 120 million in 2050 (1).

These demographic changes will have serious implications for health systems, particularly in responding to the rising burden of cancer and other noncommunicable diseases. Cancer is more prevalent in older adults with cases amongst the over 65s accounting for over 50% of the global cancer burden (2), and are often detected at a more advanced stage. When combined with the unique challenges associated with the management of cancer in older people, this growth necessitates focused attention on older populations within cancer control policy and planning. However, current evidence suggests there are limited programmes and services in place to respond the needs of this population (3).

Addressing cancer and ageing will require the engagement and support from across the cancer community to improve the comprehensiveness of care for cancer in older people. A comprehensive discussion of global priorities for geriatric oncology has recently been put forward by the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) and outlines priorities for the global advancement of cancer care in older adults (4). In this article, we explore what the cancer community could learn from approaches taken in palliative care that could inform efforts to increase access to multidisciplinary, patient-centred oncogeriatric care. We wish to emphasize that this is not a suggestion that older patients with cancer should only be offered palliative care services. Rather, we have sought to better understand what we can learn from the palliative care model as an essential component of comprehensive cancer care, and one which also emphasizes the importance of addressing the needs of a key vulnerable group.

Challenges facing geriatric oncology

Geriatric oncology is a comparatively recent branch of oncology that emphasizes the needs of older people. Its goal is to improve outcomes for older patients with cancer, recognizing and responding to the variable health status of these individuals. It seeks to establish patient-centred responses, using tools like comprehensive geriatric assessments (CGAs) to shape and prioritize multidisciplinary treatment.

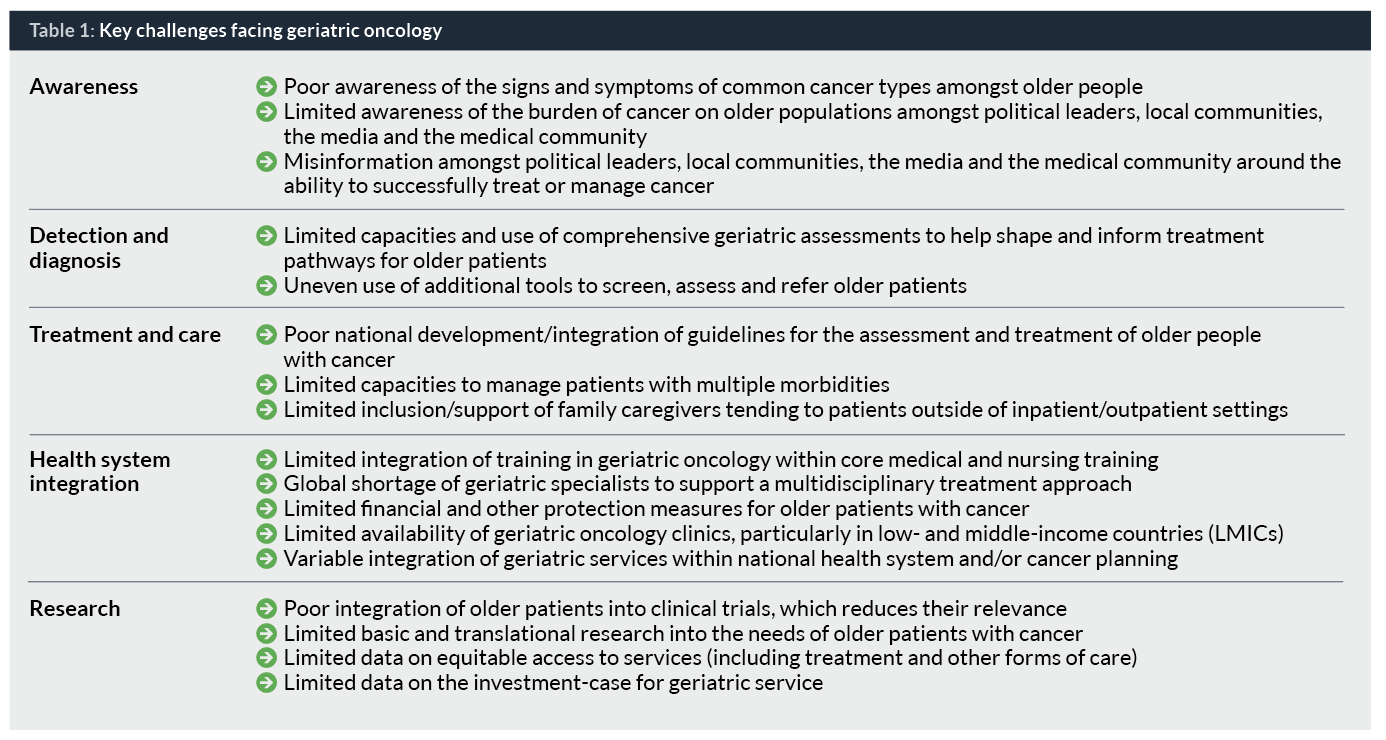

A large part of the research to date has assessed the extent to which health systems are responding to the needs of older patients with cancer, with a particular focus of maintaining their quality of life and functional capacities. The literature documents a number of successes, including the development of patient-centred treatment tools, guidelines to improve the management of comorbidities, creation of multidisciplinary teams, and research to define appropriate indicators and metrics for success (5). It also identifies a series of challenges that are limiting the introduction, scale-up and uptake of geriatric oncology services that span the spectrum of cancer control, an overview of which are contained in Table 1.

Responding to the challenges set out above will require the engagement and support of the cancer and broader health community to reform current health systems. Many of these hurdles are not new, and there are numerous different models that we can consider when thinking through how progress could be made. Given its focus on supporting the strengthening of health systems to deliver quality care, we see several interesting connections between the approach used by the palliative care community and the goals of the geriatric cancer movement. Moreover, palliative care is an essential cancer service and part of a cost-effective and integrated approach which will form an important pillar of all geriatric cancer services (6).

Scaling-up coordinated geriatric care: Learning from approaches to palliative care

Palliative care is a holistic approach that seeks to improve the quality of life of patients and their families facing life-threatening illness from the moment of diagnosis (7). It is dependent on the early identification and assessment of conditions, and responds using multidisciplinary teams to treat pain and other problems, be they physical, psychosocial or spiritual, and should not be reduced down to solely end-of-life care (8). It provides an interesting patient-centred model in which, in its optimal form, coordinates expertise from across disciplines to deliver a plan that is shaped around the needs and preferences of the patient. While many countries are struggling to deliver this universally, and there is an urgent need to scale-up access particularly in LMICs, several of the approaches used in palliative care could help inform discussions, planning and practices in the scale-up of oncogeriatric care.

Comprehensive care assessments

The first of these is a focus on developing patient-centred care, through to the use of comprehensive care assessments to shape care plans and referrals. The use of comprehensive geriatric assessments (CGAs) to develop tailored treatment plans, based on the stage of disease and capacities of patients is central to geriatric oncology. These assessments gather information not routinely captured in oncology assessments and have been found to increase the effectiveness, efficiency and quality of care. In Sweden, the use of geriatric assessments was found to both increase the cost-effectiveness of care and preserve patients’ physical fitness after hospital discharge (9, 10). Likewise, effective palliative care is centred on a robust assessment of patient needs and preferences. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) guidelines on the management of cancer pain call on all countries to make use of assessments as a starting point for action. In recent years, there has been extensive work to develop new tools to streamline this assessment process and thereby expand the settings in which assessments can take place and therefore improve their applicability. Conversely, the literature indicates that the complexity of undertaking CGAs has limited their use (11), in turn suggesting that there is a need for accelerated work to refine these tools and complement them with additional tests in order to scale-up the use of CGAs across countries and healthcare settings (12).

Inclusive multidisciplinary tumor boards

Following an assessment, the second approach focuses on establishing multidisciplinary support teams to deliver care in a timely and coordinated manner. Palliative care, where implemented fully, draws on the expertise of multiple professions and there are strong examples of countries across different income levels making progress in coordinating multidisciplinary palliative care for older populations. In the context of health budget cuts, Edmonton, Canada, developed a comprehensive palliative care service consisting of family physicians, home care, hospice, a tertiary palliative care unit, and consulting services. The focus was on building a patient-centred system and facilitating easy and quick referral through to other levels of care as needed, to increase access and minimize the use of high-cost emergency services (13). In India, the development of palliative care services has seen significant localized health system reforms to establish a network of home-based care practitioners who can draw on the services of multidisciplinary collaborations to meet patient needs (14). In oncogeriatrics, tumour boards are the primary tool for multidisciplinary collaboration and the inclusion of geriatricians is an essential quality criteria; however poor engagement or availability of geriatricians has limited their systematic use. A focus on establishing mechanisms and building stronger collaborations between specialists and levels of the health system is essential, and has been success factor in France, where networks for geriatric cancer centres have been established, but the role of geriatricians in the management of patients is still variable (15). What this suggests, however, is that integration is feasible and has the potential to increase the quality and financial efficiency of care, even amid challenging economic conditions.

Education and training

A final approach where there are fruitful parallels is in the strong focus on improving public awareness and increasing skills to deliver palliative care services. These can be broadly grouped under the heading of educational activities, which includes communication and advocacy. Using additional training to improve clinical skills and retain palliative care staff has been central to the development of palliative care services, and there are several excellent examples from India, Uganda and Kenya. Responding to the shortage of trained health workers in Kathmandu, Nepal, a short course in palliative care was established to train nurses to deliver home-based palliative care in 2016. Looking ahead, work is being undertaken to support the integration of these nurses into the city and regional health systems to improve referrals and use of their skills (16). Given the global shortage of geriatric oncology training, the use of in-service and other training courses provides an interesting template which organizations like SIOG and others are exploring, including potential synergies with palliative care competencies (17). This is being conducted alongside advocacy for the inclusion of geriatric oncology in core medical and nursing curricula (4).

In several countries, formal education of the health workforce has been supplemented with culturally relevant community-oriented educational initiatives, and collaboration with older people has helped reduce stigma and misinformation. In Uganda, a combination of media outreach and community volunteers was used to increase both provider and public awareness and this has been successful in destigmatizing death and raising awareness of the value of, and demand for, palliative care nationally (18). In comparison, the literature suggests that there is not the same demand for services amongst older populations and that this reticence to engage with health systems is resulting in late-stage presentation, poorer care outcomes and limited participation in clinical trials. Increasing awareness of the unmet needs for geriatric oncology, both amongst potential patients and decision makers, will be critical to build support for investing in the physical and human resources needed to develop or scale-up services.

Responding to outstanding challenges in geriatric oncology

While there are several valuable parallels between geriatric oncology and palliative care, the former is faced with some unique challenges to the scale-up of services. All policy and programme responses must be grounded in a robust evidence base, but for geriatric oncology there is a global shortfall in data and research. The regular inclusion of upper age restrictions for participation in research studies and clinical trials limits the applicability of study conclusions to older populations. Moreover, many countries’ national statistics do not encompass older age groups and the data that much of the global reporting depends on either do not disaggregate by age or set age caps (19). A 2018 review of national cancer control plans (NCCPs), explored a number of key metrics indicating the comprehensiveness of the planning, including the needs of vulnerable groups. However, the review did not include indicators relating to older people with cancer. Few NCCPs include attention to older populations and this is perhaps symptomatic of the limited recognition of their needs. As the foundation for national action on cancer, NCCPs represent a logical starting point for comprehensive national advocacy around geriatric cancer.

Moreover, when assessing the impact of cancer on older populations, it is vital to consider the affordability of care. As countries look to implement financial protection measures as part of the drive to universal health coverage (UHC), older people are a key vulnerable group. Affordability of care is a large barrier for older patients with cancer, particularly those individuals who may already be disadvantaged due to socioeconomic group, ethnicity or educational attainment. The long-term nature of many geriatric treatment pathways and the increasing use of novel treatments particularly in high-income countries, pose an increasing financial burden for older people with limited financial flexibility. For example, in Nigeria, only 3% of the population is enrolled in the National Health Insurance Scheme, causing older patients with cancer to rely heavily on family and community support to fund their care (21). In the United States, Medicare beneficiaries, who are largely on fixed incomes, have a mean annual out of pocket spending of US$ 8,115. Financial protection measures, such as national and non-governmental organization subsidies, and reducing cost sharing will be important to limit the financial burden of cancer care on older populations and are part of increasing health equity.

As discussions around the expansion of geriatric oncology develop further, it is important to recognize the political agency of older people in policy discussions, and the importance of engaging them in conversations at national and global levels about disparities in access to essential services. To date, these voices have been missing from the debate. In many countries, older people are an influential election demographic with the power to help drive significant reforms nationally. In Canada, 82% of people between the ages of 65 to 74 voted, compared to 50% between the ages of 18 and 24 in the 2011 federal election (22). If harnessed, this growing population could become influential advocates for increased investment in health systems, and a stronger focus on the health needs of older people.

When thinking through how we are approaching cancer and a globally ageing population it is helpful to draw on other disease programmes, including those of communicable diseases that have a strong equity focus, are patient-centred and participatory. From the authors’ perspective, the approaches used by the palliative care movement promote a holistic view of patient management and have the potential to help shape and inform cancer control programmes within the framework of a life course approach. This should not lead people to assume we can directly transpose the palliative care model, nor that geriatric cancer patients should only be offered palliative care. Instead we see this as a contribution to the necessary conversation about how we respond to the needs of the majority of cancer patients globally. As UICC, we welcome the opportunity to discuss the further scale-up of services and how different approaches can promote health equity and address the needs of older populations effectively as part of a commitment to UHC and its rallying cry to ‘leave no one behind’.

Acknowledgements

With kind thanks to the Kirstie Graham, Mélanie Samson, Zuzanna Tittenbrun and the International Society for Geriatric Oncology for their review.

Rowena Tasker, BA, MA, is the Global Advocacy Manager in the Knowledge, Advocacy and Policy Team at the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) where she focuses on global health discussions, particularly follow-up to the UN High-level Meeting on UHC. Rowena holds a Master’s in Global Health and Development from University College London and a Bachelors in Geography from the University of Oxford.

Philip Martinez works in the Knowledge, Advocacy and Policy Team of the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC). Prior to joining UICC, he had worked as a lab manager in a memory and neuroscience lab at Cornell University and clinical research assistant with the Translational Research Institute on Pain in Later Life at Weill Cornell Medical College. He is a rising fourth year at Cornell University pursuing a BS in biological sciences with a concentration in neurobiology and behaviour. In addition to this, he is pursuing minors in gerontology and business.

Dr Sonali Johnson is Head of Knowledge, Advocacy and Policy at the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC). Her main area of work is to ensure that cancer prevention, treatment and care are positioned within the global health and development agenda. She holds a PhD and post-doctorate diploma in public health and policy from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and an MSc in Gender and Development from the London School of Economics and Political Science.

References

1. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2019) World Population Ageing 2019, Highlights. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WorldPopulationAgeing2019-Highlights.pdf (accessed 25 March 2020)

2. IInternational Agency for Research on Cancer (2018) GLOBOCAN 2018, Estimated number of new cancer cases 2018, all cancers, both sexes, ages 65+ http://gco.iarc.fr/today/online-analysis-pie?v=2018&mode=cancer&modepopulation=income&population=900&populations=900&key=total&sex=0&cancer=39&type=0&statistic=5&prevalence=0&population_group=0&ages_group%5B%5D=13&ages_group%5B%5D=17&nb_items=7&group_cancer=1&include_nmsc=1&include_nmsc_other=1&half_pie=0&donut=0&population_group_globocan_id= (accessed 25 March 2020)

3. Soto-Perez-de-Celis E et al. (2017) Global geriatric oncology: Achievements and challenges. Journal of Geriatric Oncology, 8: 374-386

4. Extermann, M et al. (2020) Top priorities for the global advancement of cancer care in older adults: An update of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) 10 Priorities Initiative. Lancet Oncology (in press)

5. Extermann M (2010) Geriatric Oncology: An Overview of Progresses and Challenges. Cancer Research and Treatment, 42(2): 61-68

6 World Health Organization (2017) “Best buys” and other recommended interventions for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259232/WHO-NMH-NVI-17.9-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed 6 April 2020)

7. World Health Organization (2014) Strengthening of palliative care as a component of comprehensive care throughout the life course (resolution WHA67.19) https://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s21454en/s21454en.pdf (accessed 6 April 2020)

8. World Health Organization (2020) WHO Definition of Palliative Care. https://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ (accessed 25 March 2020)

9. Lundqvist M et al (2018). Cost-effectiveness of comprehensive geriatric assessment at an ambulatory geriatric unit based on the AGE-FIT trial. BMC Geriatrics, 18(1), 32.

10. Åhlund K et al (2017). Effects of comprehensive geriatric assessment on physical fitness in an acute medical setting for frail elderly patients. Clinical interventions in aging, 12, 1929–1939.

11. Terret C (2005) Geriatric Oncology – a challenge for the future. European Oncology Review, 24-6

12. International Society for Geriatric Oncology (2020) Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) of the older patient with cancer. https://www.siog.org/content/comprehensive-geriatric-assessment-cga (accessed 3 April 2020)

13. Fainsinger RL, Brenneis C, Fassbender K (2007) Edmonton, Canada: A Regional Model of Palliative Care Development. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 33(5): 634-639.

14. Rajagopa MR et al. (2014) Creation of Minimum Standard Tool for Palliative Care in India and Self-evaluation of Palliative Care Programs Using It. Indian Journal of Palliative Care, 20(3): 201-207

15. Sifer-Rivière L et al. (2011) What the specific tools of geriatrics and oncology can tell us about the role and status of geriatricians in a pilot geriatric oncology program. Annals of Oncology, 22(10): 2325-2329

16. Shah BK, Shah T. (2017) Home hospice care in Nepal: a low-cost service in a low-income country through collaboration between non-profit organisations. The Lancet Global Health, 5(1): S19.

17. Hsu T et al. (2020) Identifying Geriatric Oncology Competencies for Medical Oncology Trainees: A Modified Delphi Consensus Study. The Oncologist (in press).

18. Fraser B et al (2017). Palliative Care Development in Africa: Lessons from Uganda and Kenya. Journal of Global Oncology, 2018:4, 1-10.

19. HelpAge International & AARP (2019) Global AgeWatch Insights 2018: Report, summary and country profiles

20. Romero Y et al. (2018). National cancer control plans: a global analysis. Lancet Oncology, 19(10): e546-e555

21. Kiri VA, Ojule AC (2020). Electronic medical record systems: A pathway to sustainable public health insurance schemes in sub-Saharan Africa. Nigerian Postgraduate Medical Journal, 27(1): 1-7

22. Uppal S, LaRochelle-Côté S (2012). Factors associated with voting. Perspectives on Labor and Income, 24: 1-15

population=income&population=900&populations=900&key=total&sex=0&cancer=39&type=0&statistic=5&prevalence=0&population_group=0&ages_group%5B%5D=13&ages_group%5B%5D=17&nb_items=7&group_cancer=1&include_nmsc=1&include_nmsc_other=1&half_pie=0&donut=0&population_group_globocan_id= (accessed 25 March 2020)

Soto-Perez-de-Celis E et al. (2017) Global geriatric oncology: Achievements and challenges. Journal of Geriatric Oncology, 8: 374-386

Extermann, M et al. (2020) Top priorities for the global advancement of cancer care in older adults: An update of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) 10 Priorities Initiative. Lancet Oncology (in press)

Extermann M (2010) Geriatric Oncology: An Overview of Progresses and Challenges. Cancer Research and Treatment, 42(2): 61-68

World Health Organization (2017) “Best buys” and other recommended interventions for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259232/WHO-NMH-NVI-17.9-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed 6 April 2020)

World Health Organization (2014) Strengthening of palliative care as a component of comprehensive care throughout the life course (resolution WHA67.19) https://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s21454en/s21454en.pdf (accessed 6 April 2020)

World Health Organization (2020) WHO Definition of Palliative Care. https://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ (accessed 25 March 2020)

Lundqvist M et al (2018). Cost-effectiveness of comprehensive geriatric assessment at an ambulatory geriatric unit based on the AGE-FIT trial. BMC Geriatrics, 18(1), 32.

Åhlund K et al (2017). Effects of comprehensive geriatric assessment on physical fitness in an acute medical setting for frail elderly patients. Clinical interventions in aging, 12, 1929–1939.

Terret C (2005) Geriatric Oncology – a challenge for the future. European Oncology Review, 24-6

International Society for Geriatric Oncology (2020) Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) of the older patient with cancer. https://www.siog.org/content/comprehensive-geriatric-assessment-cga (accessed 3 April 2020)

Fainsinger RL, Brenneis C, Fassbender K (2007) Edmonton, Canada: A Regional Model of Palliative Care Development. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 33(5): 634-639.

Rajagopa MR et al. (2014) Creation of Minimum Standard Tool for Palliative Care in India and Self-evaluation of Palliative Care Programs Using It. Indian Journal of Palliative Care, 20(3): 201-207

Sifer-Rivière L et al. (2011) What the specific tools of geriatrics and oncology can tell us about the role and status of geriatricians in a pilot geriatric oncology program. Annals of Oncology, 22(10): 2325-2329

Shah BK, Shah T. (2017) Home hospice care in Nepal: a low-cost service in a low-income country through collaboration between non-profit organisations. The Lancet Global Health, 5(1): S19.

Hsu T et al. (2020) Identifying Geriatric Oncology Competencies for Medical Oncology Trainees: A Modified Delphi Consensus Study. The Oncologist (in press).

Fraser B et al (2017). Palliative Care Development in Africa: Lessons from Uganda and Kenya. Journal of Global Oncology, 2018:4, 1-10.

HelpAge International & AARP (2019) Global AgeWatch Insights 2018: Report, summary and country profiles

Romero Y et al. (2018). National cancer control plans: a global analysis. Lancet Oncology, 19(10): e546-e555

Kiri VA, Ojule AC (2020). Electronic medical record systems: A pathway to sustainable public health insurance schemes in sub-Saharan Africa. Nigerian Postgraduate Medical Journal, 27(1): 1-7

Uppal S, LaRochelle-Côté S (2012). Factors associated with voting. Perspectives on Labor and Income, 24: 1-15